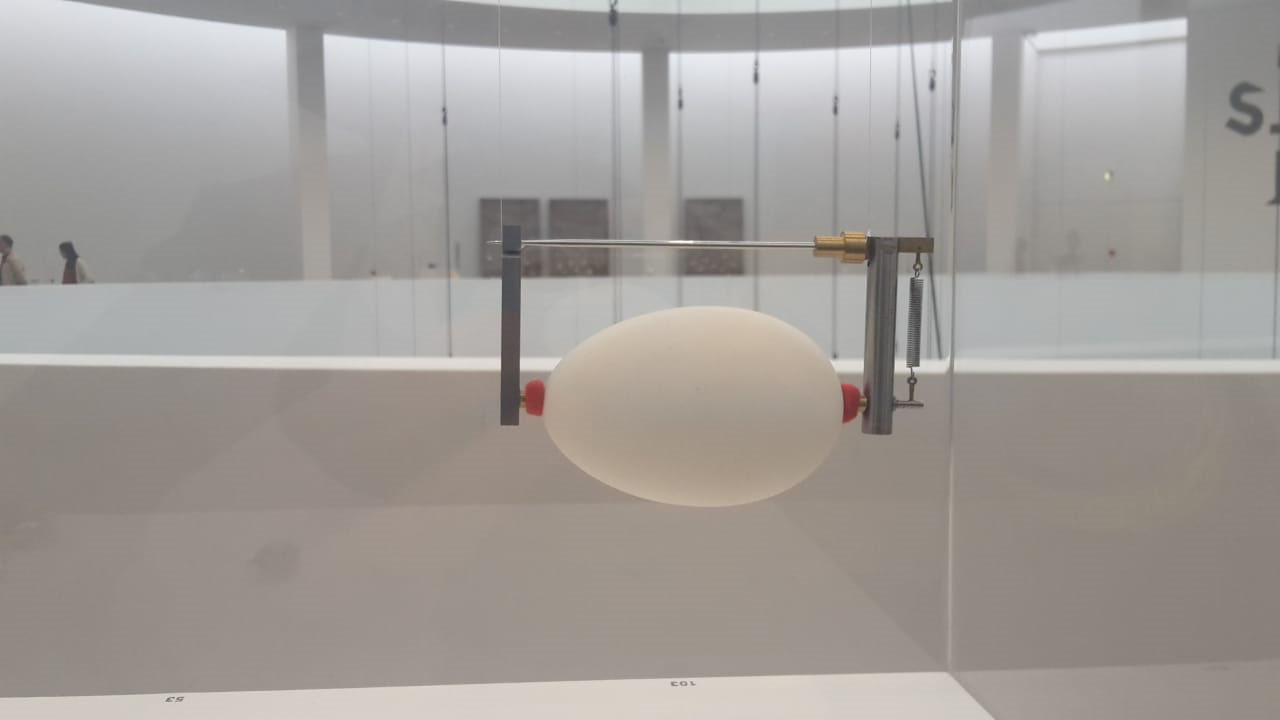

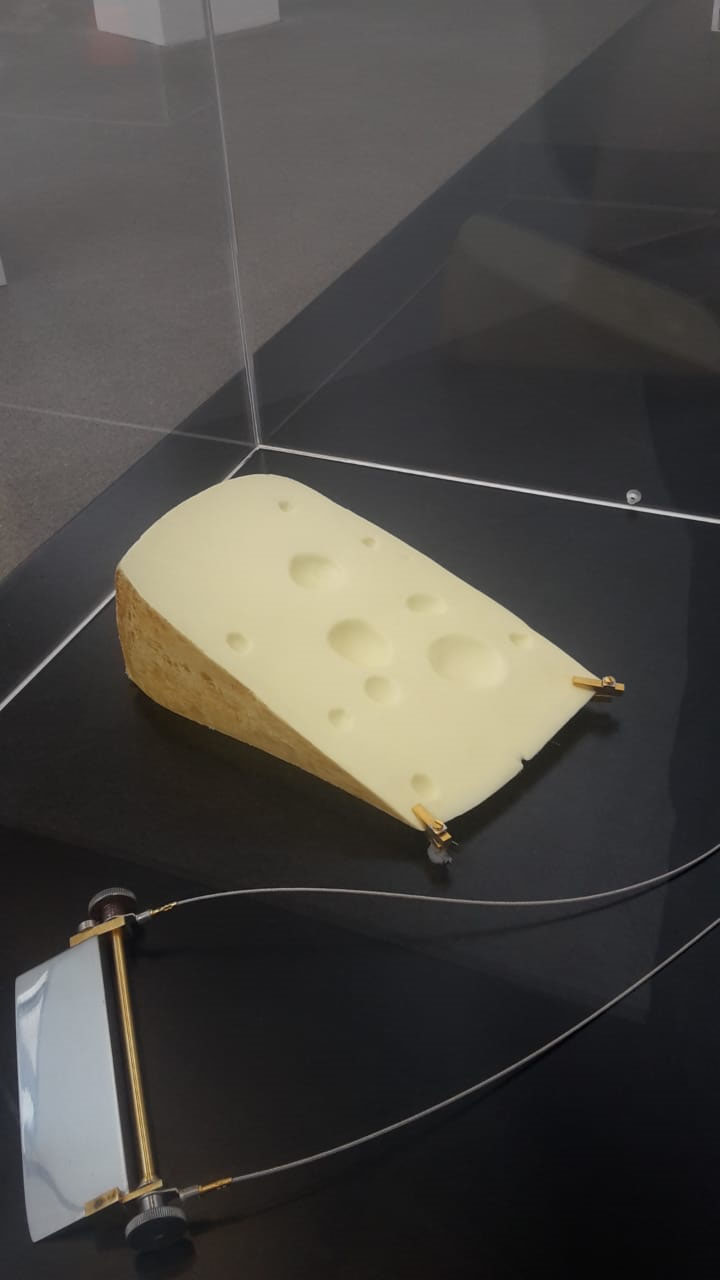

Whoever visits the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich and goes up to the rotunda on the top floor of the building designed by the German architect Stephan Braunfels (1950) and inaugurated in 2002, will be confronted with a series of goose or ostrich eggs. Holes, or rather emptied and hanging from a thread, a cable or a gauge. And a little further, with a piece of cheese made of wax, held by small golden clasps. And with natural sponges and cardboard containers, soaps, balloons and shoe soles always linked in or with scientific instruments, cables and everything that serves to measure, specify or connect these and other elements in a whole as absurd as those constructions that They are admired in the cabinets of wonders of the Renaissance and Baroque palaces.

Here, as there, there is an abundance of eggs, coconuts, shells and corals assembled or combined with wood and precious metals to transform them into something else, that is, into a human work, useless - or better it would be to say useless -, which exalts admiration for the forms of nature. Among them, that of the pearly nautilus of the Indo-Pacific seas, a species of a genus of cephalopod mollusks that is considered a living fossil and whose shell, sectioned sagittally, reveals a line of nacre and is arranged forming an almost perfect equiangular spiral, an example of the golden spiral. Nautilus shells were abundant in Renaissance curiosity cabinets and can today be admired in some museums mounted on a thin pedestal, sculpted or wrought in the manner of an extravagant cup intended primarily for decoration rather than use.

In fact, one could say that the exhibition at the Monegasque Pinacoteca is a collection of curiosities from another era if it were not for the fact that the things that are combined there date from today. Or yesterday. As proof, the assembly of another object well loved by goldsmiths three and four centuries ago is worth it: the gallstones of a mother, in this case that of the Norwegian artist Sigurd Bronger (1957), a craftsman and jewelry designer, the author of the objects exhibited in this exhibition that bears the title “Trag-Objekte” in German and “Wearables” in English. A somewhat difficult translation but whose idea could be something like “portable”, “wearable” or “usable”. Bronger considers himself more of a jeweler than a goldsmith, a fundamental difference when looking at these objects that no one wears on the street, but they are defined as jewelry that, in some way and with humor, celebrates the connections that industrial society has been able to establish. Some call them "wearable instruments" and consider them somewhere between jewelry, art, design and engineering, a demonstration of the technical prowess of Bronger, a 21st century jewelry and assembly engineer from discards and remains. and of history.

Born in 1957 in Oslo, the capital of Norway, Sigurd Bronger attended the Vocational School in his hometown, specializing in jewelry, for a year before choosing to study watchmaking and goldsmithing at the Schoonhoven Vocational School in the Netherlands. , where he graduated in 1979. After his studies, he worked as an engraver at the Royal Posthumus Factory in Amsterdam, founded in 1920 and dedicated to clichés, stamps and printing plates. In 1983 he returned to Oslo, where he has lived and worked since then. Bronger first exhibited solo at Kunstnerforbundet in 1990, and then began to collaborate regularly with the Gallerie Ra in Amsterdam. His international breakthrough came after his solo exhibition at the National Museum in Stockholm in 2005, while in 2011 he had a major exhibition at the Lillehamme Art Museum.

He won the David Andersen Design Competition in 1987, received the Arts and Crafts Prize in 1995, the Norwegian Goldsmiths Association Design Prize in 1996 and 2004, and the Jacob Prize in 2010. His objects have been acquired by the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Het Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, the National Museum in Stockholm and the Kunstindustrimuseene in Oslo and Copenhagen. In 2015 he received the Prince Eugene Medal "for his outstanding artistic achievements." In 2009, Die Neue Sammlung in Munich invited Sigurd Bronger to give a lecture on his work as part of the “All About Me” series. Two years later, the museum added the Camay Necklace to its collections, which it made in 2005, the only Bronger piece in a German museum. In 2016, he was awarded the Bavarian State Prize for his work “Transport Device for a Nautilus”. The works exhibited in the Pinacoteca come from private and public collections around the world, from Austria, Denmark, France, Great Britain, Italy, Luxembourg, Poland, Sweden, the Netherlands and Thailand to the United States.

Bronger, in fact, considers himself a master of his craft as a jeweler and goldsmith. The works, unlike the ready-mades of the 20th century, come from his hands, from his machines and from his workshop, not from others. And, as can be seen in Munich, the repertoire of things elevated to jewelry objects has no limits. Objects become wearable or portable or usable thanks to the ingenious mechanisms in which Bronger mounts and hangs them. With meticulous precision, he assembles brass and gold mechanisms that he assembles like scientific instruments and, in their own way, the objects fit into the wooden cases made for the purpose. For Bronger, his works are not jewelry, brooches, rings or necklaces, but simply "wearable objects." The mechanisms that give them that character also give them entity, and as happens in a museum with the frames, the pedestals, the labels, they take them out of their everyday implications to contemplate them aesthetically in their unexpected beauty.

Bronger's exhibition is in some way related to another recently held at the Prado Museum dedicated to the frames and the reverse of great works: samples intended to recognize the layers of what we see, the human strata that make up a work of art and that is presented as a natural object. Bronger's objects are made up of others that belong to the universe of discards and other historical constellations, they are jewels that we would never attach to our clothes as a decorative element. Who would think of hanging the sole of a shoe or camel dung? Actually, a few: there, in Oxford at the beginning of the 19th century, there was the Buckland couple who, due to her interest in paleontology, she, Mary Morland, had earrings made from fossil dung. Without forgetting the egg collectors, who paid real fortunes for the empty shells of the birds that their parents had just extinct.

Portable objects, useless objects. A whole category, a whole metaphor. But also a description of the things of this world.

* Special for Hilario. Arts Letters Trades