On May 6, 1854, the Association of Friends of the Natural History of Plata was established for “the conservation and promotion of the Museum of Buenos Aires”, with the aim of “increasing its stock with productions from the three kingdoms; with anatomical preparations, and archaeological, numismatic, &a. objects, that are worthy of being exhibited, or that can be used for the study of sciences, letters and arts.” Under the initiative of, among others, Francisco Javier Muñiz, Manuel Ricardo Trelles (1821-1893), Manuel J. de Guerrico, Santiago Torres, Teodoro Álvarez and José Barros Pazos, Rector of the University of Buenos Aires, the directive commission would determine the admission of the donations received, trying to “establish a periodic publication in which the works of the partners, or of any other person related to the Museum and Natural History, are published whenever the majority of them request it.” The society took charge of promoting the museum until 1862, transferring it from the convent of Santo Domingo to four rooms of the university, on the corner of Perú and Alsina streets.

The funds would come from membership dues, from which jobs would also be provided. The Statutes regulated: the "Museum Manager" would be a Government employee "regardless of his duties as a member of the association." On the other hand, each semester, the Board of Directors would appoint a partner in charge of the care and preservation of the existing objects, together with the employee, who would monitor the scrupulous fulfillment of his general duties and the orders received from the President of the Association. Chapter 10 of the Statutes dealt with “the donations” mentioned in the attributes and functions of the Board of Directors, through one of its members, they should be made. In this sense, the Commission and the Association tried to regulate the limits of Natural History, preventing the museum from continuing to be subject to the disorderly will of citizens willing to deliver relics, rarities or unwanted inheritances. The objects of natural history and of the other branches defined in the statutes had to be deposited with the Person in Charge of the Establishment for their placement and conservation; On the other hand, purchases in money - from the Government or from individuals - would be placed in a savings account.

The twelve chapters and 63 articles of the statutes were approved by the Minister of Government and Foreign Relations of Buenos Aires, Ireneo Portela, in April 1855. Trelles was Secretary of the Association and presented his memoirs. He recognized that the history of the museum became difficult because “it had no archive”. For the people of Buenos Aires, in 1856, the Museum was experiencing a prosperous moment, a harbinger of a better future. “Son of patriotism”, torch of activity and progress, the progress of the Museum “contributed to exalt the time in which it was being carried out”. Trelles considered Natural History, the central object of the museum, as the "science that has deserved to be called the mother of all, because they all have their origin and foundations in it."

Manuel Ricardo Trelles poses in front of the daguerreotypist. 1850 / 1857. National Historical Museum. Buenos Aires. (MHN 8950)

The Association was a collegiate body. According to the statutes, the task of promoting the museum was not an individual company, not even the Government, but rather a task of qualified citizens, controlling each other and petitioning the State. In 1856, Trelles saw the future of things with optimism, stating:

“As soon as the superior decree of May 6, 1854, which created the association, was known to the public, the Museum began to receive the testimonies of the general acceptance that the thought that inspired it deserved, inside and outside the country. From everywhere, and from all kinds of people, he received that proof every day. It could be said that nature raised its reals then and set off towards Buenos Aires to deposit its offerings in the new temple that was erected to worship science.” (Trelles, 1856: 8)

So many objects were received that in two years the amount accumulated in the previous three decades had doubled. The Association, on the other hand, appointed the members of the number set by the statutes, electing seventy-eight honorary members and seventy correspondents. From the payment of the membership diploma (one hundred pesos each) and the semi-annual fees in 1855, 10,860 pesos had been obtained, which, by 1856, had risen to 15,000. The donations of the partners, correspondents, heirs and circumstantial interns show the weight of collecting in the sociability of these counties.

The donors, mostly gentlemen – with the exceptions of Dionisia Maldonado, Gertrudis Rodríguez Peña de Olavarría and Felipa Segismundo de Laprida who, respectively, donated a camoatí, a portrait of Nicolás Rodríguez Peña (Gertrudis's brother) and “two crystallizations, one sample of agate from the Eastern State, 83 shells and two marine plants”- will be presenting, individually, things of varied origin. Only one donation comes from the Government and another, that of a monstrous calf, from a group such as the editorial office of “La Tribuna”.

The heirs of the priest Saturnino Segurola were in possession of something they did not want to keep and handed over to the Public Museum the objects from the cabinet of the deceased who, in life, had collected samples of the customs of exotic countries, a coin and shells, relics of the English invasions and the history of the city, minerals, plants and hard parts of rare animals. Segurola had also been interested in "chinoiseries", like the young Emilio Bunge, who, without thinking that several decades later he would be Mayor of the Federal Capital, delivered a Chinese book, an imperial edict, a theater advertisement and cigarettes, objects that, added to the shoes donated by the Segurola, showed that from the Plata the English expansion in China and also in India was accompanied.

Many donations relate to international trade and travel routes of the time. Dr. José María Uriarte, future director of the Insane Asylum, had taken care to witness an itinerary with material -and mineral- memories of Tenerife, Vesuvius, Pompeii and Italica, emulating the eighteenth-century Grand Tour and the routes of the German romantics , English and French. The histories of the museums often leave aside this collective aspect of the constitution of the collections and focus on the task of synthesis of their directors or of those consecrated by historiography as central figures or founders of the disciplines. The list of donors, however, shows that the individuals were part of a local and international social network for the exchange and sale of natural history objects, rarities, money, and historical “relics”.

The objects delivered to the Museum inscribe the individual itineraries in a whole where they dissolve. Trelles, in reporting on the objects brought into the museum, would only highlight some of the names of the donors whose private interests appear in the things they give away. Likewise, they show the order of the inventory prior to the classification presented by Trelles. The scientific vocabulary of the 18th century (“petrifications”, “madrepores”) coexists, for example, with nomenclatures that are the result of comparison with the daily life of the collector (“petrified sweet potato”, “petrified willow and carob tree”).

The smelting of metals and the disappearance of forms aroused the collecting desire of many, as can be seen in the donations of nails and other objects accidentally melted as a result of the fires. The presence of objects made by the contemporary Indians of the Pampas and the Chaco and of antiquities from Peru, Bolivia and the Old World contrasts with the lack of archaeological objects from those "Argentine" territories where minerals, fossils, birds, mammals, historical relics and the different phenomena of nature.

The first donation was made by Trelles himself on March 15 and consisted of fragments of fossil animals from the Pampas as well as a shell of the emblematic animal of South America: a mataco or armadillo. The number and type of donations exceeded those of Natural History and do not appear to have been turned down. Quite the contrary, the donations shaped the museum and created a balance between natural history and other branches of knowledge, thereby drawing criticism from foreign visitors. The donations adopted a spontaneous and pragmatic form that, in some way, continued Manuel Moreno's suggestion of the year 1824: the museum would be established “with whatever there was”. Trelles clarifies: "the Public Museum of Buenos Aires, despite the fact that its main object is Natural History, is nevertheless a general Museum that brings together all kinds of objects that can be used for the study of sciences, letters and Arts".

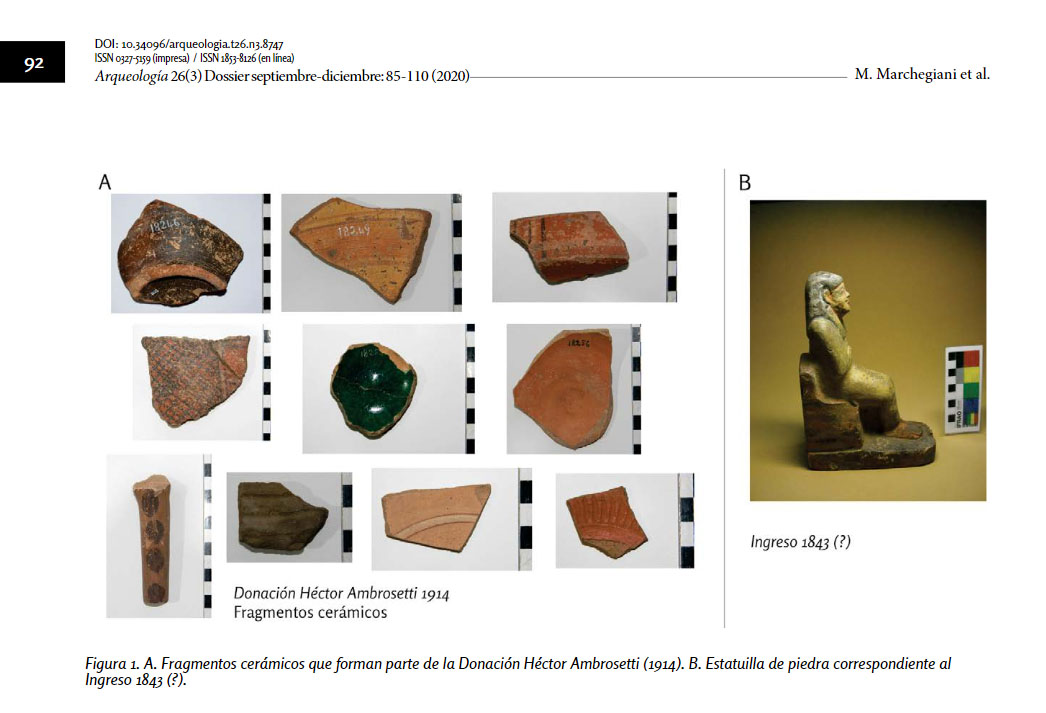

Thus, the Museum, in 1856, could be considered divided into six sections, one for each kingdom of nature (Zoology, Botany and Mineralogy), two for Numismatics and Fine Arts, and the sixth for various branches. The latter, composed for "all the objects that are not included in the previous ones, and that, due to the various branches to which they belong, cannot form separate sections" suggests that the acceptance of donations could not be ruled as the statutes declared and, that Instead, they forced to create a section outside the declared interests. As "several" were grouped, among other objects, "an Egyptian statue" donated in 1843 by Tomás Gowland (1803 - 1883), a member of the association, an English merchant who, with his parents and brothers, had arrived in Buenos Aires in 1812, where, in the late 1820s, they associated with George Washington Slacum, United States consul. As Maxine Hanon tells it, he was the owner of the famous “Casa delhammer”, an auction firm that lasted until 1870. Thomas Gowland was the forced auctioneer of the British of Buenos Aires, “rich and poor, diplomats, reverends, hoteliers or merchants, everyone entrusted him with the sale of their furniture when they decided to move or leave the city.” Of well-known public performance, in the first years of the Association of Friends of Natural History, he exercised his mandate as deputy of the province. Perhaps the Egyptian statue came from one of those auctions, a gift, or a trip. Anyway, today we invoke it as one of those fragments of Egyptomania that in recent decades had invaded Europe and, apparently, reached the Río de la Plata.

The remaining “several” included mosaic samples from the pavements of various temples in Herculaneum and Pompeii (donated by the honorary member Uriarte); a collection of vases and objects from ancient Peruvians (donated by Antonio Miguel Álvarez, perhaps an inheritance from his father, Ignacio Álvarez Thomas from Arequipa), high-relief geographical maps (donated by the Prussian consul Friedrich von Gülich), weapons and objects of use of the savages of America (donated by several partners) and many other objects not listed.

The Fine Arts section, with just five pieces in 1854, now had 35, "without artistic merit but to be preserved as historical monuments." This section included the portrait of the twelfth Bishop of Buenos Aires, another of General Beresford, that of two soldiers from the 6th Campaign Regiment from the time of Rosas, and the portrait and statue of Baron Alexander von Humboldt, donated by von Gülich.

In 1854, the Zoology section had 1,475 objects and, since then, had acquired another 2,052. Trelles classified them according to the order of the zoological classes: Mammals (here including man, quadrupeds, vespertilians, quadrupeds, cetaceans, and fossil bones), Birds, Fish, Shellfish, Reptiles, Insects, and Monsters. The classification combined several classification systems. This section, on the other hand, was the most difficult to preserve since "the beings destined to compose it are by natural law despicable after life, and all the preservatives and care that are used to preserve them, as long as possible, are few. to contrast the law that fights them”. Somehow, a Museum was presented as the space that sought to stop the inexorable laws of time and destruction through various artificial resources: the most effective preservatives and the appropriate furniture and cabinets to store the pieces, which would avoid the immediate influence of the atmosphere, the invasion of dust and insects. Added to this, the joint action of daily vigilance dedicated to facing any threat and "an intelligent trainer who, at the same time that he uses the most effective methods to preserve, has extensive knowledge in the animal kingdom, so that his works give life to death itself.” For this, it was necessary to equip the Museum. In the Zoology section, there were quadrumans, insects and birds from the country and from other places in South America, including some from Brazil, presented by the founding partner, the landowner Manuel José de Guerrico, today considered "the first art collector with that Argentina told“, but that, apparently, did not rule out natural history.

A part of the collections related to human beings were located in this section of Zoology. Among them, the mummy from Egypt and her sarcophagus covered with hieroglyphics, which, since there was no local paleographer to decipher them, it was unknown who was dead. The mummy, like the other zoological specimens, showed signs of deterioration: “Our humid temperament is ungrateful to it”, affirmed Trelles, but, except for this consideration, it did not generate any doubts about where it should be housed. In the Zoology section, in addition to the Egyptian mummy, there were quadrumans, insects and birds from the country and from other places in South America, including some from Brazil, presented by the founding member Manuel José de Guerrico.

From the order given to the collections, it stands out that these objects placed in "several" do not seem to be enough or indicated to start an archeology section, despite the fact that the statutes speak of promoting the acquisition of archaeological objects. On the other hand, the Egyptian mummy was included in the Zoology section, to represent the group of humans, separating it from the statue of the same origin donated by Gowland and which was deposited in "several". Trelles is prioritizing a "natural" criterion rather than geographical or cultural, grouping things by their place in the kingdoms of nature. A more than interesting position for the Buenos Aires of that time: a conclusion of the Linnaean order of the world but that would soon acquire other meanings.

* Irina Podgorny is the author with Maria Margaret Lopes of The Desert in a Showcase. Museums and natural history in Argentina, published in Mexico in 2008 and republished by Prohistoria editions (Rosario) in 2014. These lines are based on chapter 3, "Nature on the march towards Buenos Aires."